STOCKHOLM WANTS TO BECOME THE WORLD’S FIRST CLIMATE-POSITIVE CITY AND PETROFAC IS HELPING THEM GET THERE, WITH THE DESIGN OF A NEW FACILITY THAT WILL CAPTURE THE CARBON DIOXIDE FROM THE CITY’S BIOMASS-FUELLED POWER STATION

THE HEAT IS ON

PROJECTS

Stockholm is one of Europe’s most environmentally friendly cities. The Swedish capital has been an international role model of global environmental and climate action for decades and its current Climate Action Plan pledges that the city will be fossil-free by 2040 – and potentially the world’s first climate-positive capital city.

Key to achieving this ambitious target will be a new carbon dioxide (C02) capture facility at a combined heat and power plant run by the city’s energy company, Stockholm Exergi. The bioenergy plant will be able to capture 800,000 tons of carbon dioxide per year – equivalent to the current annual CO2 emissions from all the traffic in Stockholm.

“The goal is that all Stockholmers should be able to take a hot shower and know that they simultaneously remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere,” as Stockholm Exergi’s research and development manager Erik Dahlén puts it.

Petrofac was awarded the Front-end Engineering Design (FEED) contract for what Chet Biliyok, Technical Director, New Energy Services describes as a first-of-its-kind project – and one of the most exciting prospects he has worked on in a long career specialising in carbon capture solutions.

WORDS RICHARD LOMAX

PUBLISHED JUNE 2022

Swedish chic: The Värtan power plant is the world’s largest – and most stylish – urban bio-fuelled cogeneration plant

Hot potassium scrub

“The technology we are working with has never been deployed at this scale for this purpose before,” Chet says. “It uses hot potassium carbonate, basically salt, to ‘scrub’ the CO2 from the flue gas.

“But what is really exciting is the potential. There has never been a better time or place to be launching this. The project has received €180 million from the EU’s Innovation Fund, covering part of the deployment cost and the operating capital for 10 years. And as CO2 will be captured from the combined heat and power plant that burns forest residue in its boiler, it means that CO2 will be removed from the atmosphere, resulting in negative emissions that can be sold off as carbon offsets.

“With the price of CO2 hovering above 80 euros per tonne for much of this year on the EU emissions trading scheme (ETS), there’s a powerful financial justification in Europe for CO2 Capture and carbon offsets.”

Get this right, he says, and it opens up a huge market, as companies like Microsoft and Google scramble to offset their carbon use and historical emissions (Microsoft has set up a US$1-billion fund to invest in carbon reduction and removal technologies, while an alliance of Silicon Valley companies including Google, Meta (Facebook) and Shopify announced in April 2022 the purchase of $925 million in carbon removal over the next eight years).

But there are a few big challenges on the Stockholm project to overcome first, which is where Chet and Petrofac’s engineering team in Woking, England have been focusing their attention with a target completion date for the FEED by end of May 2022.

“The world will be watching – and from industrial sectors beyond our traditional focus.”

CHALLENGE 1: the pioneer’s risk

Firstly, this is pioneering technology. Chet has been involved in carbon capture technologies for much of his career, both as an academic – he was Research Fellow and visiting lecturer at Cranfield University in the UK – and as a practitioner, working on the Peterhead CCS project, a first-of-its-kind implementation of CO2 Capture on a gas-fired power plant in Scotland. He has a deep understanding of the technical challenges ahead. But there are risks, he says.

“It’s a common misconception that CCS hasn’t been done commercially before. CCS plants have been operating for four decades in North America, where the economics have stacked up – the CO2 is sold to oil companies who inject the gas into their reservoirs to extract more oil and gas. They use chemical compounds called amines, which are efficient but have health, safety and environmental challenges. What’s unique with the Stockholm Exergi project is that we’re using hot potassium carbonate that relies on an innovation by CO2 Capsol.”

Sweeter solution

Amine gas treating, sometimes called ‘sweetening’ in the oil refinery business where it’s used to remove the foul-smelling sour gas hydrogen sulphide as well as CO2, is the standard process. The most commonly used amine solvent Monoethanolamine (MEA) reacts strongly with acid gases like CO2 and can capture up to 90% of the CO2 from the flue gas of a fossil-fuelled plant, but it’s an energy-intensive process requiring large facilities - and the amines can be carcinogenic as they degrade. A lot of thinking goes into the engineering and operations that make amines safe for flue gas applications.

Hot potassium carbonate – ‘hot’ because the absorber that captures the carbon operates at 115 degrees C – is a less reactive chemical but can be adapted for deep CO2 capture from flue gases, along with efficiency, cost and environmental benefits – important to the client. Capsol’s End of Pipe technology is a stand-alone solution that connects to the flue gas duct just before the stack (the tall vertical pipe that power plants use to exhaust combustion gases into the air. Its height helps disperse pollutants over a wider area). The flue gas is compressed to the point that the hot potassium carbonate solvent easily absorbs the CO2 from the flue gas like an amine. Capsol’s innovation is that most of the energy used for compression is recovered as electricity and heat, boosting the overall efficiency of the plant.

The captured CO2 will be compressed, liquefied, then transported and stored in sub-sea geological aquifers or in depleted oil and gas fields in the North Sea.

CHALLENGE 2: FORM AND FUNCTION

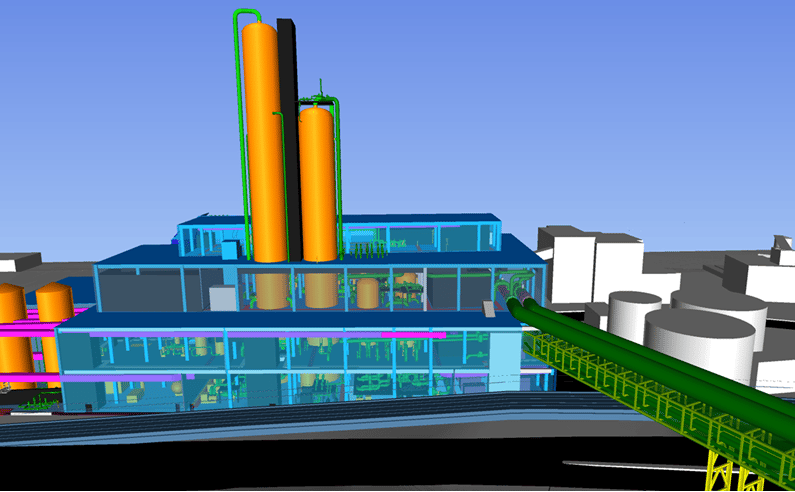

A second challenge is the location. “There are significant aesthetic considerations in a city like Stockholm,” says Chet. “It’s a beautiful place, so anything we design must not detract from that appearance.”

The Värtan power plant is the world’s largest urban bio-fuelled cogeneration plant, but it’s got a strong claim to being the most architecturally stylish too. The overground part of the plant has been clad in a curved façade of vertically arranged ceramic tiles, reducing its acoustic and visual impact and winning an award for its Swedish architects. It will be a hard act to follow.

The building that will house the capture plant will be designed with walls lined with acoustic louvres to keep the noise levels down, guarantee good ventilation to keep operators comfortable and safe, and maintain the attractive façade of the entire facility.

CHALLENGE 3: Space

The third consideration is space constraints. The plant is in the capital’s port district, surrounded by water where space is at a premium. It needs to be a compact design. And finally there is the challenge of integrating the facility into the combined heat and power plant, in a way that doesn’t disrupt the operation of the plant, which provides heating, cooling, electricity and waste management services to Stockholmers.

Better by design: 3D model of the plant

The world is watching

Petrofac is the integrator on this project, which will eventually require the entire value chain to demonstrate the same carbon-neutral or negative credentials. At peak periods up to fifty people, engineers with transferrable expertise from the oil and gas sector, have worked on the FEED from Petrofac’s centre of excellence at Woking. They have been supported by the company’s engineering teams in Chennai India.

“After the FEED we will be hoping to bid for the EPC,” says Chet, “and at that stage, which would involve substantial supplier selection and management, the focus in terms of resourcing would shift to Sharjah as well as a strong presence in Stockholm.”

“The world will be watching,” says Chet, “and from industrial sectors beyond our traditional focus.”

In the past it has cost nothing to emit CO2, but at a price of CO2 now well above 80 euros per tonne and with the price expected to rise further with ETS reforms, carbon capture and storage is viable for many industrial sources of emissions.

“A carbon adjustment border tax will be implemented within the next couple of years in the EU too, which would extend the price to other jurisdictions exporting goods and services to the EU,” says Chet.

The European Innovation Fund is supporting Stockholm Exergi’s project for negative emissions because it believes it has the potential to transform the European energy industry once it becomes operational in 2025.

If Stockholm, birthplace of course of a certain Greta Tintin Eleonora Ernman Thunberg, does achieve its ambition of becoming the world’s first climate-positive capital by 2040, Petrofac will have played a small but important supporting role.